How many of us buy a product and are so sure we know how to use it, we skip reading the instructions? WD40 is a great example. It is an excellent lubricant for door hinges and other squeaky places but it is not appropriate to use as a killing spray. I mention this because I have had homeowners call in to tell me strange things over the years...just to kill a bug.

The instructions or rather the label tells you just how that product is approved to be used and how it could harm you, your family, your pets or the environment. If you use something off-label, you actually are breaking a federal law. Read the small print, it usually says, "It is a violation of Federal Law to use this product in a manner inconsistent with its labeling."

Labels are very interesting if you take the time to read them. On labels for products we use to manage or kill a critter, it will include how to protect you, the sprayer, as well as directions on how to apply the product; precautionary statements for humans, domestic animals and the environment; types of personal protection clothing and equipment recommended and even what to do if you spill it. The signal words listed (caution, warning, danger) are not how effective the pesticide will be in killing something but rather how dangerous it is to you, the human.

You may not know this but in NC, if you spray for pay, like a landscaper, you must have a registered pesticide license with the NC Department of Agriculture. The goal is to protect the public health, safety and welfare, and to promote continued environmental quality by minimizing and managing risks associated with the legal use of pesticides.

Pesticide applicators attend regular classes to keep their license, often offered at local Cooperative Extension offices (you can read more here http://go.ncsu.edu/pesticide). Applicators are continually reminded how to read the label, how to calibrate equipment properly, how to calculate application rates and integrative pest management or IPM methods.

IPM is an approach to managing a problem pest (critter, fungus or bacteria problem) so examples include scouting regularly for pest populations, identifying it is an actual pest that needs to be managed, determining the least toxic methods to control (pick off the bug and squash), trying to convince a client 10 bugs is not usually a problem, and many others. There are many tools at our disposal to try but it is not a guess. Research is constantly being done at our universities on what is the most effective control that also saves money and has the least impact humans and on the environment. Each State even publishes a manual to follow annually (NC Agriculture Chemical Manual) that our applicators use. There are general public suggestions as well but the manual lists chemical names rather than brand names so as not to favor one company over another.

Cooperative Extension provides technical advice to anyone on how to control most pests with a combination of techniques and tools (your neighbors or their dog do not count). Sometimes pesticides are the best available option with the knowledge we have now. It is so easy to look back and say what idiots we were way be when...think DDT-infused wallpaper for the nursery (Woman's Day ad in 1947).

There are other ways to be less harmful to our beneficial critters.

1) Learn to live a few ugly plants and a population of bugs and critters.

Only 1% of our bugs are actual pests that could harm something and even less that are interested in humans. Squishy yards from mole tunnels will not last forever and the moles are actually doing you a favor by truly aerating the soil!

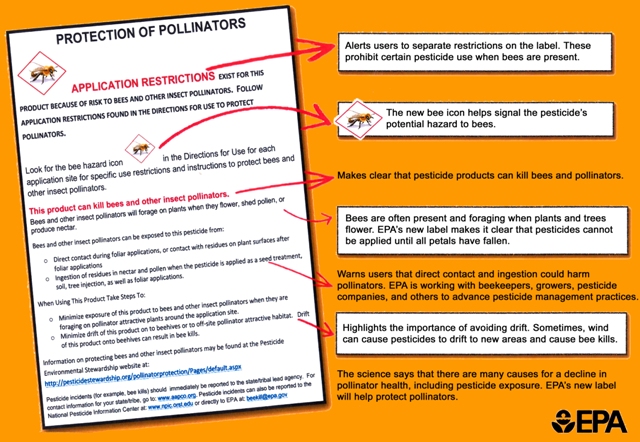

2) If you use pesticides of any kind, read and follow the label to apply correctly. More is not necessarily better. Timing is also critical. When bees are in flight, you should not treat flowers.

In fact in the last year and a half, Forsyth Cooperative Extension educated hundreds of Piedmont Triad landscapers about a new bee advisory box that will be on pesticide labels, once the rotation makes it to shelves (this was actually incorporated in 2013 by EPA; read more http://go.ncsu.edu/epa-bees). It provides application restrictions on all pesticides that pose a risk to bees and other insect pollinators.

3) Consider whether you really need to use a pesticide and if you need help determining another option, call your local countyCooperative Extension office for advice.

For example, a common product we use as a dust on flowers to protect the aesthetics from hungry caterpillars can actually be carried with the pollen back to the hive, potentially causing a pesticide build-up or even killing the colony. Use granulars, solutions and soluble powders instead that can easily break down or are least toxic. Bacillus thuringiensis (Bt) is a bacteria that controls bad caterpillars with little to no risk to good bugs (bad bug species are actually a tiny percentage of the population).

4) Add more flowering plants to the landscape; particularly more natives plants.

All pollinators need flowers but honey bees need 2 million flowers to make one pound of honey. Three great publications you can find online (http://gardening.ces.ncsu.edu/publications-3/) or at many local Extension offices are: Managing Backyards and Other Urban Habitats for Birds, Butterflies in Your Backyard, and Landscaping for Wildlife with Native Plants.

5) Participate in the Bee Buffer Project and set aside 0.25 to 3 acres with a free U.S. Bee Buffer seed mix.

You must have a NC residency, be committed to keep the buffer in place for 3 years, be willing to allow researchers on-site occasionally and be open to providing feedback. Read more at http://beebuffer.com/ on how to get involved.